Ghosts of the Forest

THE STORY OF THE GHOSTS, OR HOW TO BUILD A FOREST

by Jesse Jarnow

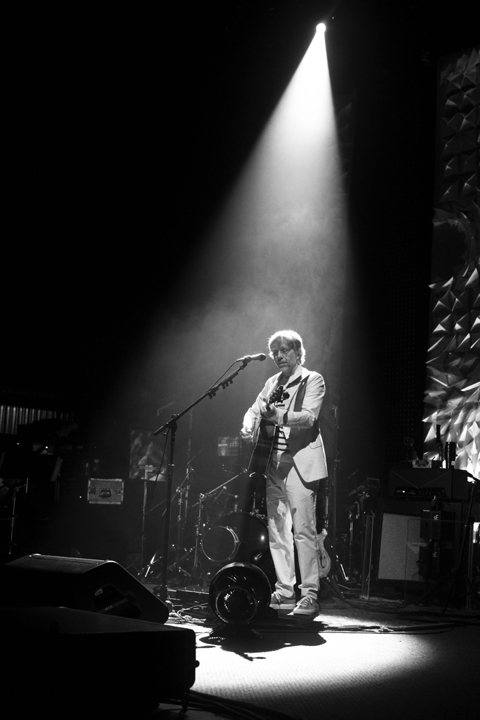

Trey Anastasio: It’s my favorite thing to do. It’s so scary. I walked out on stage in Maine, on the first night of the tour, and it was so different.

Over a 35-year career, Trey Anastasio has performed in a rock quartet and with symphony orchestras, with cosmic free jazz big bands and Broadway pit musicians, with collaborators he’s had for decades and players he’s only just met. However, Ghosts of the Forest constitutes something new for him. And not just new in the sense that of an original album and limited edition band, but a new kind of new altogether.

Ghosts of the Forest–the album and ten live performances with an additional dozen songs–remains its own body of work, self-contained and unlike anything else in Trey Anastasio’s career: a crafted stage show with two hours of unheard music, deeply personal lyrics, and platforms for improvisation.

In part, the project was a tribute to Trey Anastasio’s close friend Chris Cottrell, who succumbed to adrenal cancer in January 2018. Not long before, Anastasio had lost his sister. And, just after Cottrell’s passing, Trey Anastasio Band keyboardist and old friend Ray Paczkowski fell ill with a brain tumor. It was a tumultuous and emotional time. Anastasio enlisted close musical friends Jon Fishman and Tony Markellis, and eventually Paczkowski himself.

But despite its introspective roots, spectral name, and the radical notion (for Anastasio, anyway) of performing a fixed song-list each night, Ghosts of the Forest was hardly a grim monument. In tribute to Cottrell, who loved the adventurous side of his friend’s bands more than anything else, Ghosts of the Forest became a container for the present moment — and each ensuing present moment that existed as the project unfolded.

There was an album, too, released on the eve of the tour. But, as with much of Anastasio’s music, it was most alive during performance, a tangible and illuminated thread. Lift the bell jar and see.

Trey Anastasio: I’m kind of always writing, so I think something was being born, and I didn’t quite know where it was going. And then this thing started happening with Chris. But the project was actually started before that became the event of the day. I try to keep a “no resistance” relationship with music, just open and in the present moment all the time. So, then, things that happen in the present start to affect the direction of where things are going. And my experience–sitting with Chris in his last moments, drifting in and out of sleep–is what informed it and shaped it into what it was. It grew in an organic and natural way, because of the timing of all this.

After this whole thing was over, I started thinking that it had just happened so fast, this outburst of music, writing and arranging and playing. I found myself asking, “what was I lamenting here?” Everybody’s friend dies. It was a profound loss, but It still felt like there was more beneath the surface. It really haunted me.

I’ve been trying to put two and two together after the fact. I think a lot of it is about the loss of that naive feeling, all that stuff you feel when you’re a kid. And when that goes away you have to get a new mojo. And maybe that’s what it was about — more than the loss of an individual person, that this was the person that tied me to my childhood outside my work world. He was a tether to “Let’s go ride a fuckin’ raft down a river in Utah and camp out for six days in a tent,” which we did, and look back and realize you’re really not supposed to put a tent right next to a river because the river rises sometimes and people die. But we did that. It was stupid, but it never even crossed our minds. Eventually, you get too old to live that way anymore. It’s right around the age that I am now. So maybe this is more lamenting the loss of that than an individual.

Ray Paczkowski: When I was in the hospital, Trey would come over all the time, and we were talking about Chris and what happened to him. I’d known Chris for many years. It was kind of surreal to be in a hospital room, and I wasn’t sure what was going to happen, but I was pretty sure it’s going to be fine, because that’s what I was told. Trey was definitely a little crazed about it all, that I might be headed off into the other world. I think when Trey freaks out, [his personality] just gets even more Type A.

Don’t mistake the ghosts for the forest.

Where Phish have become infamous for never repeating a setlist, playing more than 230 different songs during their 13-show Baker’s Dozen run at Madison Square Garden, Ghosts of the Forest negated the notion of setlist score-keeping almost entirely. During their 10-show tour in April 2019, the band performed a fixed sequence of music. As Anastasio points out, the project wasn’t a theater piece. But it wasn’t quite a rock concert either. While the music was rehearsed and tight, and even scripted to some degree, there was flexibility and room for improvisation.

Anastasio and Phish have escalated their game over the years, from one-night-only big picture set pieces to slower long-term evolutions. But Ghosts of the Forest stands alone as a single focused moment, a standalone two-and-a-half-hour night of music consisting of 21 songs, a four-piece band, two additional singers, and staging by Abigail Holmes, meant to be performed and experienced live. It also represents perhaps his biggest step as a lyricist. Often a collaborator, Anastasio’s truly solo compositions likewise thread through his career, his lyric writing growing more nuanced and personal over the course of decades. Ghosts of the Forest represents the largest and most cohesive batch of lyrics entirely by him, and unquestionably the most personal.

Trey Anastasio: Chris was an elk hunter, but he wouldn’t get an elk most years, he just loved being high up in the Rocky Mountains. He told me that there was this Native American term, “ghosts of the forest,” to describe elk, because they would vanish into the woods when you are tracking them. They’re very hard to hunt. He’d told me how he’d be following a trail, and it would suddenly just end, as if the herd had all leapt sideways. You never knew when the trail would end.

Finally, one year he got an elk. He was all alone when he shot the elk, and he told me about this eye contact moment. It gave me chills. He dressed the elk in the proper way, which he was very proud of, and carried the elk meat all the way down the Rocky Mountains alone, hundreds of pounds of it. I would come over, and he would serve it to us. It lasted for a long time. There was an elk rug on his floor when you walked in his house.

It was the only elk he ever got, but I remember there was a change. There was a sense of pride, a spiritual shift. I could tell when we talked that it was a very big deal to him. It made me reassess my point of view about hunting, because there was nobody who loved nature more than Chris. When he died–and I was sitting with him, playing guitar, as he drifted into the spirit world–I thought back about that.

Helping to build on the narrative was Abigail Holmes. A concert design veteran with a multi-decade genre-spanning resume, one early credit that attracted Anastasio was her work with Talking Heads during their pivotal Stop Making Sense tours. Serving as lighting director for the genius re-imagining of a live rock performance–a show that a teenage Anastasio caught several times–Holmes worked with David Byrne again recently on his spectacular fusion of color guard and live music, Contemporary Color. She’s partnered with Janet Jackson, The Cure, and Roger Waters, helping the Pink Floyd songwriter stage The Wall in Berlin. She’s collaborated with longtime Phish lighting director Chris Kuroda to design the band’s last two light rigs, including the bold LED screens that surrounded the band in 2016, as well as the new movable rig that debuted in 2017. Anastasio enlisted her as a collaborator before the Ghosts even had a discernible shape.

Trey Anastasio: Abbey [Holmes, production designer] and I started to meet early on. We had coffee before I even finished writing the songs. She was kind of talking to me as it was being written, and we would talk about theatrical concepts. We talked about why you need to be, as an artist, completely concrete in the narrative and the intent behind every line, in every musical choice — even though it’s not important that the audience exactly knows my concept. But if I put nonsense in there, their radar will go off.

From a musical perspective, having Fish and Tony seemed like a place to start. They’re my close friends, which was important based on the subject matter. And it was important that it was neither Phish nor TAB as a starting place, and we started off just the three of us.

Jon Fishman: There was also a very clear element of Trey saying things like “I’ve always wanted you and Tony to play together. I kind of play with a certain abandon. And Tony plays with a certain grounded-ness. He can definitely stretch out and I can definitely tighten up, but he’s very grounded. You never have any fuckin’ doubt where the one is when you’re playing with Tony, or where the groove is, or the feel. And that makes it easy for me to get a little bit wild-eyed and play to the edge of my skill set.

Tony Markellis: I’ve been fortunate enough to play with a lot of great drummers over the years, but Jon is a whole different animal. His playing is such a balance of delicate detail with explosive, raw animal energy — a rare combination of freedom and precision. I’d go so far as to call his drumming melodic.

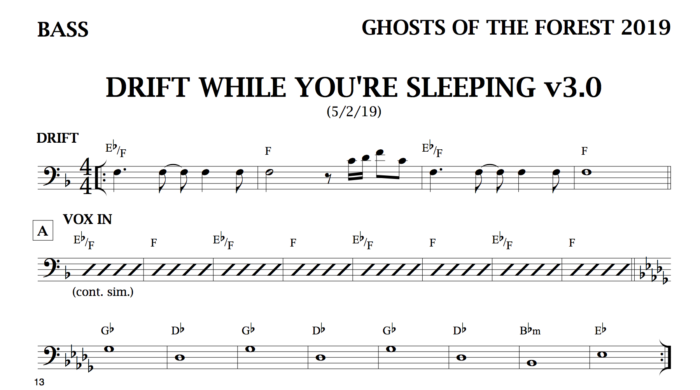

Trey Anastasio: Tony likes charts, so I’d make a chart for Tony. With Fish, I sent him [demos of] all the songs and he just went home and practiced. He’s a practice addict. He showed up knowing everything. For “Drift While You’re Sleeping,” he came up with this beautiful drum part that’s all sculpted.

Jon Fishman: I love every single one of these songs. As a songwriter, I think Trey really upped his game with this particular material. Not that the material suddenly became serious in the sense that there’s no humor to it. But, you know, Trey’s sister passed away. His best friend passed away. There was a scare with Ray. There’s a lot of death around us. Things get real. I think there was a focus on the realness of life as he experienced it up to this point, and trying to say things in a straightforward manner, and not sugar-coating. The focus was on the realness of the life experience and the beauty of the world, and the beauty of music.

Trey Anastasio: After Chris died, and I’d finished making the album, I went on a cavern tour in Utah, next to a Navajo reservation. I had a Navajo guide who started talking to me about elk. He said that when a boy turns into a man in his culture, they go hunt for an elk with a bow, and when they shoot the elk they become a man. They believe in this passage of the elk’s spirit to the natural world.

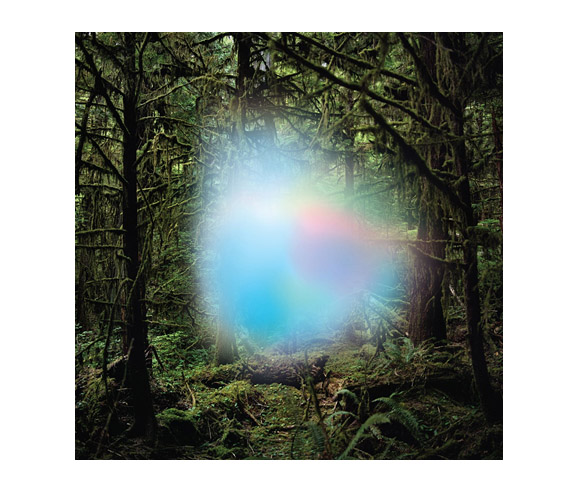

And, when the guide told me that, my head was exploding. I’d just finished the album, and the very beginning of the album–the very first lyrics of the opening song–was my attempt to write from the point of view of the elk, as Chris and the elk make eye contact in the woods: “And you’re the one to take me down, so take me down.” The Ghosts of the Forest idea is that Chris has now died and gone to that spirit world; they are together, one spirit, and that’s what the album cover eventually became, the spirits commingling in the woods.

***

PART TWO: GROWING GHOSTS

At first, Ghosts of the Forest was only envisioned to be modestly ambitious. Anastasio would record a nine song album at his Barn studio in Vermont in the spring of 2018, just a few months after Chris’s death. He would be joined by Phish drummer Jon Fishman and Trey Anastasio Band bassist Tony Markellis, with TAB keyboard player Ray Paczkowski adding keyboard parts not long thereafter. There would be a staged component, and the shows would perhaps blend the new material with more familiar numbers from the songbook. However, the project began to evolve.

Trey Anastasio: Pretty early on, “Beneath the Sea of Stars” was the song that pointed me in the direction of doing a whole live show as a narrative journey. That was when there were only nine songs. It was the last song on the record, and I was thinking of lost family members and friends, Chris, my grandparents, my sister. The Barn is in the woods and full of my grandparents furniture from my childhood, so I think of them a lot.

That song is set up like a long night in the woods, you hear the hooting of the owls, and we go into the woods together with the spirits. Then it gets darkest before the dawn, in that trippy section, and then in the middle there’s a sunrise moment: “morning birds arc in magnetic parade and the dawn is slowly breaking.”

The morning brings a little clarity and hope and spirituality with the “blue all around” part, but at the end, reality hits again and we kind of smash back through the glass right back into the confusion from the beginning of the album. This feels accurate to me when it comes to grief, at least in my experience. A brief glimpse of the big picture, followed immediately by, “Who cares about your stupid concept? I’m just sad. I can’t get over this shit, it’s breaking my heart, and I’m really depressed. Stop telling me they’re in a better place.” So that was a conscious choice to make the album loop back around in a cycle.

I think that song was sort of the trigger point for creating a whole show.

I wanted this to be different than Phish. It should be one set, not two. Pretty early on, it was conceived as a journey, an emotional journey.

Abigail Holmes: They were really wonderful conversations, exploring this wonderful new music, the great musicians who would be playing it, and the best ways to frame that experience on stage. We met on and off over time, which was cool. That let us talk about ideas for the show, and then gave some time to think about things and work on them. And come back and look at them and talk about the next step. Some things really stayed constant throughout, and others we’d come back to and maybe say, “yeah, that’s cool, but not right for this show.” There was enough time to let things develop and then let things go.

Although Anastasio had ventured into musical theater with Hands on a Hardbody (2012), the truer lineage of Ghosts of the Forest’s staging might be found in the challenge of introducing new music to audience members with expectations of hearing their favorite songs.

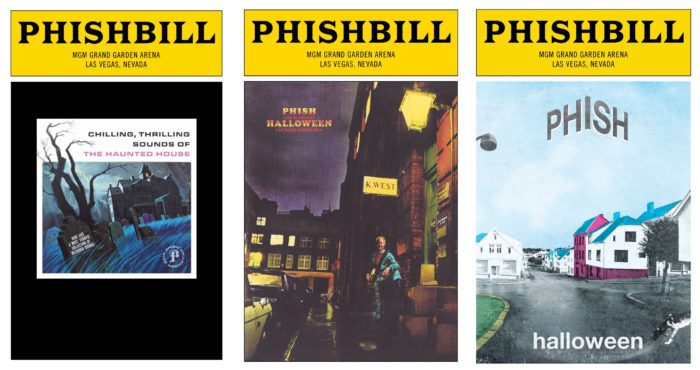

Phish made a low-key art-form of rolling out their new material in creative ways. In 1992, they accompanied their latest batch of songs with a musical secret language, in part to measure how quickly fans spread the tapes. In 1995, there was a whole album’s worth delivered at a Voters For Choice benefit a month in advance of their summer tour with enough time for the recordings to spread before the band hit the road. In 1997, a set of all-new songs (played twice) at the backyard Bradstock gave way to a tour where the band shelved many classics. Since 2011, Phish’s Halloween performances have become a way to launch new material into their repertoire, vacillating with Phish’s typical slipperiness between silly and serious, including 2013’s Wingsuit (which would become the 2014 album Fuego), 2014’s Thrilling, Chilling Sounds of the Haunted House, and 2018’s í rokk, performed in the guise of Kasvot Växt.

Trey Anastasio: I learned from Wingsuit. We put people in the difficult situation of trying to grapple with something they couldn’t viscerally latch onto, and I don’t think it went all that well. As soon as it was over, I was like “whoops, we should have started with ‘Fuego,’” which is what the album ended up starting with. “Wingsuit” is a song we were really excited about, and I still am, I just don’t think it should have started the whole thing off.

Then, the next time we did it, it was Chilling, Thrilling Sounds, and I thought we should start with eleven absolutely visceral dance grooves before the band even got together. The idea being that we’re gonna do this again, but that there was a skill set that was carried forward, so we didn’t make that same mistake again. Instead, we’re going to come out with a bang. We’re going to give people something that they can have fun with, and allow them to come on the journey with us. And then the roof is going to blow off and it’s going to be fucking fun.

Then the next time was Kasvot Växt, where we’re going to do it with more elaborate songwriting, where we really try to say something, and it’s gonna be a party, and the first song is gonna go bang, the stage is going to be white and you can’t take your eyes off it, and it’s a really heavy dance groove. Everybody’s invited to the party. By the end of the first song, I wanted to honor the audience by inviting them on the journey with us and not giving them something that’s difficult to wrap their brains around — because that’s our responsibility.

This time [with Ghosts of the Forest] what was really scary was going a giant step even way further into the personal, honest, and the emotional. It was a risk to walk on stage to a sold out house and know that all I have to do is turn around say “’Sand,’ one, two, three…” and the whole fuckin’ place goes nuts — and not do it. And [then] start singing these songs like, “I’m sad that you died,” and “I feel uncomfortable in my own skin” and “I’m about to run” and all this shit, and not have any idea how people are gonna react.

Abigail Holmes: I’ve been at many Phish shows. I worked with Chris Kuroda on the production design of the recent layout with the moving trusses; and on the show prior with the video surfaces. One thing about the Phish audience is their loyalty, and their level of engagement. It is amazing to be able to make completely new music with a new band and have the audience ready to come and experience it. That is incredible, because it allows risk taking and experimentation. And I think that the audience knows it’s reciprocated. Trey thinks deeply about how the audience is going to respond. We talked a lot about the audience — their expectations, what was going to be different about this show, having moments they would relate to, and also taking them to some new places, and how to find the best balance of those things.

Trey Anastasio: It’s kind of built to be finite. I’m going to try this experiment, I’m going in full, I’m diving in completely. I’m going to let the chips fall where they may, despite doubts. I knew everybody was gonna fuckin’ rock out to Kasvot Växt, because it was built that way. Whereas that wasn’t true on this one. This was part of the conversations with Abbey, about how the production is going to unroll one song at a time. There are no flashing lights. Every piece of production is going to be built on 100% emotion. I’m going to start off with this really slow, sad piano thing. We’re not going to rush it. It felt really revelatory.

Abigail Holmes: There is a strong sense of place in many of the songs, being out in nature where Chris lived, the idea of Ghosts of the Forest. I had the feeling from listening to the songs that this was partly a real place, but also a mystical place. In my thinking, ideally the visual design would help the audience enter into a sort of journey with the musicians, enter into a world where this music would be played and shared, and step out of the everyday for the time of the show.

Trey Anastasio: That was definitely the stated goal — that there was a sequence of events. It was laid out almost with some of the rules of theater, the main rule being that I know what the whole narrative is, and that Abbey followed the same direction. Even though all the visuals were abstract, she listened to all the lyrics and the music and knew why she making every choice that she made; they were all conscious choices to further the emotion or meaning of the song. Anytime it started to get too literal, she would take it out. She didn’t want a literal definition. There was intent, that was the keyword. There was intent behind every visual based on the meaning of the song to her, and there was intent in every sequence to further the story. That’s where it was different than a Phish show. A Phish show is visceral in the purest sense of the word, the real definition, which means in the muscles of the heart.

Abigail Holmes: We would definitely have an idea for the meanings that the visual design choices were representing — but they were absolutely intended to be abstract enough that the audience could interpret and relate to them individually, not to be so literal that they defined things too completely. It was important to leave space for people to experience it in their own ways. For visuals, I mostly think this was done in a subtle way–a shift in color, or brightness, a change in the video–always meant to enhance what the music was saying.

Trey Anastasio: It’s not a theater piece, but there are skills I picked up along the way to make things carry more emotional weight. You learn little tricks along the way, like the 11 o’clock number, which is a term from the golden age of Broadway, a theatrical tool, the big break-on-through number. In Gypsy, it would be “Rose’s Turn,” where Gypsy Rose leaves, and her Mom has a full-on breakdown and realizes her plight. The character often changes. They call it the 11 o’clock number, because shows in the golden age of Broadway used to end at 11:30. “A Life Beyond the Dream” felt like that song.

There are all these tricks that people have learned from hundreds of years of doing live theater, live performances. Every time I do one of these things, I figure out something new. Doing Hands on a Hardbody taught me so much that I use habitually now — for instance, how to run a rehearsal, how to get more out of a finite rehearsal.

So, with Ghosts of the Forest, I really needed to do this thing that we did with Kasvot Växt, and have some nice moments in the night where people can grab onto a visceral drumbeat for relief. Otherwise it’s too much. With Kasvot Växt, I used these mouth drumbeats that I put on my phone, and I brought them all in and Fish laid them all into grooves, which is where the songs started. So I wrote 26 more Kasvot-style drumbeats, and asked Fish–since he was going to be in New York–if he would mind going into the studio with me on January 1st and recording them all.

Jon Fishman: Phish played New Year’s Eve in New York City and on New Year’s Day–the morning after we just did this four-night run at Madison Square Garden, so I’m in great drumming shape–I went into the studio with Trey. We went to a studio a few blocks from the hotel, and he’s got 25 or 26 mouth drumbeats on his phone. There’s a drum kit set up, and Bryce Goggin had it mic’d up, and I played them. Some of the beats were a little weird, because drum machines and people singing into a phone don’t care where things are on an actual drum set. But all of it was pretty simple because you can only do so much with your mouth at once. What’s great about it–and I feel like I should do this–is that you see things that you wouldn’t play necessarily right out of the gate, so that makes your limbs move in combinations that you wouldn’t have done otherwise necessarily.

There were 15 or so that made it to potentially being songs, from which 10 or something eventually made it to the stage. He sent me the tape of these developed songs, now with some lyrics, guitar, and drums that he and Bryce had spliced together. Some of it, they would take one drumbeat and marry it to another one, and build the song with a bridge and verses and stuff.

Ray Paczkowski: It was uncanny. Trey was telling me that he would go, like [sings mouth beat] and Fish went through it and what he ended up with was the verbatim of what Trey was singing. Trey played it for me. It wasn’t, “I’m gonna take this idea and make a rhythm out of it,” it was, “this is the rhythm and I’m going to make the drums sound like [sings mouth beat].”

“Wider” song progression samples

Trey Anastasio: I knew how it was going to end and knew how it was going to start. I knew from day one that was going to end with that “blue all around” [from “Beneath the Sea of Stars”] wrapping back around. I knew the islands where it was going to go in the middle, that “Beneath the Sea of the Stars (Parts 1 & 2)” would be three-quarters of the way through. So then it was, “How are we going to get into ‘Beneath the Sea of Stars’?” And that was “Green Truth.” That was one of the drumbeats.

***

Jennifer Hartswick [vocals]: I loved this music. I came in after the recording process, so I came in with really fresh ears to a project that was basically complete. The first time I heard any of the music was when I heard the record, and I was driving, just weeping. I had to pull over, not necessarily from the sadness, but the intensity of the music. I feel like it was written with a different purpose than anything Trey had written before, and played with a different intent.

Ray Paczkowski: It was really a one-of-a-kind thing. The music that came out of all of this has that emotional quality to it. But the songs were just unique, too. The first track on the album [“Ghosts of the Forest”], I’ve never heard Trey do something like that, just the perfect melding of an odd time-signature.

Trey Anastasio: Kasvot Växt, Ghosts of the Forest, and [the staged New Year’s version of] “Mercury” all happened in a nine-month period. That’s 30 new songs and two essentially new songs with near-full production in less than a year. Part of why it works is because I learned how to prepare and run rehearsals. You do enormous amounts of prep work before you get there and you know exactly what you want to accomplish with the limited time. You bring appropriate charts and you sketch it, which leaves space in rehearsals for the most important part, which is being open and free with the band and production team. By preparing, you don’t leave these massively talented musicians standing around getting bored while you try to make up your mind. Everyone is present in the room and together we fly. I mean, look at what Abbey did. That’s a pro. She did it all before she did it, then at rehearsals she was wide open.

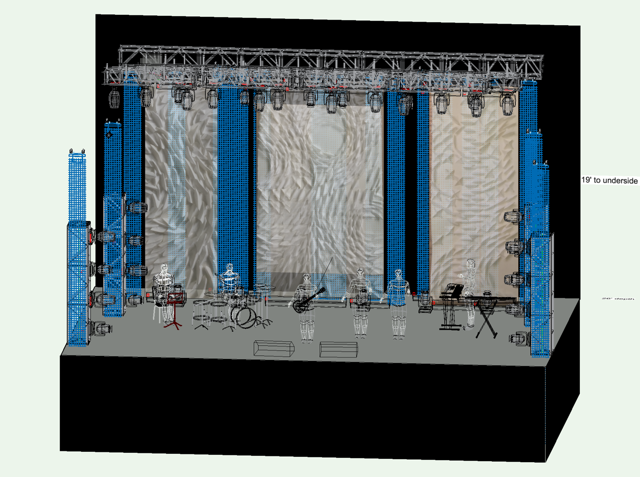

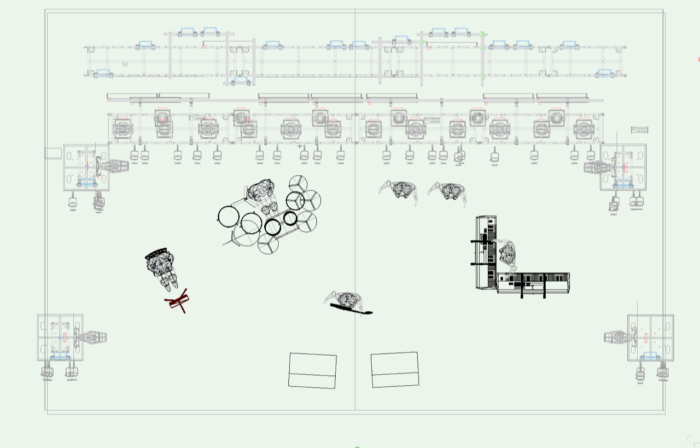

Abigail Holmes: The backdrop was one of the first elements in the design. I had been making some paper art, just for myself. As we talked about the project, I had the idea that those pieces could be the basis for a backdrop. Since the original paper pieces are handmade, there is a very organic quality to them. The pieces are placed slightly differently, shaped slightly differently. The dimensional pieces of the drapes were applied by hand, they feel very different from something which is made by machine. That seemed true to the nature and forest references, the raw quality of the emotional content of some of the songs, and the nature of the band and how they played.

Trey Anastasio: The backdrop was a roll-uppable piece of fabric that she sculpted, while listening to the music, based on her interpretations of the music. It was very integrated. She designed the backdrop that almost looked like metal. She crafted it on a piece of paper, which is now framed and hanging right in front of me as we speak in my home. She built it like it’s a sculpture, with little folded pieces of paper, then had somebody fabricate it out of fabric in such a way that it looks like the original.

Abbey laid out exactly where the band was set up. It looked so good. She would send me stuff and I would make suggestions. For instance, Tony likes to be not on the hi-hat side of the drums. He’s told me that over the years. And Fish told me that he likes to turn his head to the left when he plays, and that way he can look at my right arm, so if I start to speed up or slow down he can go with me.

She decided that she wanted Jennifer and Celisse in between the fabric pieces, standing in a row. I had told Abbey that I wanted the vocalists to be able to disappear from the audience’s view, when the four of us start jamming. But I didn’t want anybody to see them walking off stage, I wanted them to vanish. That’s why they weren’t on the other side of Ray. Abbey also told us that if our clothes were camel-colored or white, we would disappear into the background more easily, so I found a camel-colored jacket and a white jacket and Jen and Celisse also dressed in that color scheme.

Abigail Holmes: The patterns of the drape and the thin vertical panels of the LED were partially conceived as non-literal woods, the shapes on the drape nodding to the filtered light [as seen] through leaves in the woods. They were designed to allow a sense of depth, so the visuals could sort of float or recede in portions of the show. Maybe that could feel like a disconnect from an everyday reality, and create space around the music, let it be expansive.

About a month prior to production rehearsals, I spent several days with a programmer workshopping the visual ideas in a 3D rendering set-up. Trey spent time with us, and we tested the live camera effects used for the song “About to Run”, and other video imagery. That was a good opportunity to talk more about the shape of the show, and narrow the direction for some things, so we could make the best use of production rehearsals.

Jennifer Hartswick: When you’re working with somebody else, I won’t say working for somebody else, but when you’re responsible for carrying out their vision, I will very often rely on what it is that person wants: What are you looking for? What do you hear? And [on Ghosts of the Forest] it was met every time with, “What would Jennifer Hartswick do?” “Should we come in the second time?” Trey would just smile and say, “What would Jennifer Hartswick do?” And so it becomes really personal, too. Like, “Well, I’d do this, if I were me.”

Celisse Henderson [vocals]: It’s infectious. It’s impossible to be around that energy and not feel incredibly grateful. You can’t have much of an ego about anything when you’re opposite someone who’s in charge of everything, and is the best at everything, and also is so eager to learn, at every moment.

Jennifer Hartswick: For what was only a very short tour, there was an enormous amount of work and thought and care that went into it. Because ideally that’s how you want to birth something, but also if you’re paying homage to your best friend who passed away, you want to do it exactly right.

Celisse Henderson: Sometimes you lose a little perspective about what the thing is and how it reads in the house, because you’re on the stage. The sound set-up is so incredible, they’re multitrack recording everything. Trey went home and listened through, and at the beginning of one of the rehearsals on one of the days, we went and sat and watched and listened. The initial idea was to ask them to cue up certain places, to look at this, and try this, but we were all so stunned and how everything sounded and looked with Abbey running through her cues. Trey would call up a certain number, and they’d use that as a rehearsal for the lights. So we got to sit out and experience what it was and what it looked like and what it sounded like, and it was pretty incredible. It made all the things we were doing make a lot more conceptual sense. When you’re standing on stage, and there are lights everywhere around you, with a beautiful backdrop, the gravity can be hard to read because you’re inside it. But being out there and seeing how magnificent it looked, more than anything, it was invigorating!

Trey Anastasio: We had a dress rehearsal where I actually took the band out into the room and made them watch and listen to the way they were playing while watching the production, which was hugely successful. It was actually the turning point. On “Beneath a Sea of Stars,” I think there was a little bit of fear happening, that people felt like they had to play too much because it was so gentle. And then I had everybody come out and sit in a semicircle and watch what Abbey was doing with the production while the tape of the band played. And the next time they went up on stage, they got it. It gave people the confidence to be spacious and slow and patient.

Jennifer Hartswick: We had the luxury of having several sets of rehearsals. We would all meet up in New York for four days, start feeling out what felt right. We multi-tracked every rehearsal, and by the end of the day our entire multi-tracked rehearsal was in a folder, and we could go back and listen to it and say “I liked this,” “let’s do this,” or whatever. It’s extreme. No one else I’ve ever worked with does anything like this. It’s blowing Celisse’s mind. She’s like, “Is this normal?” And, yeah, it is.

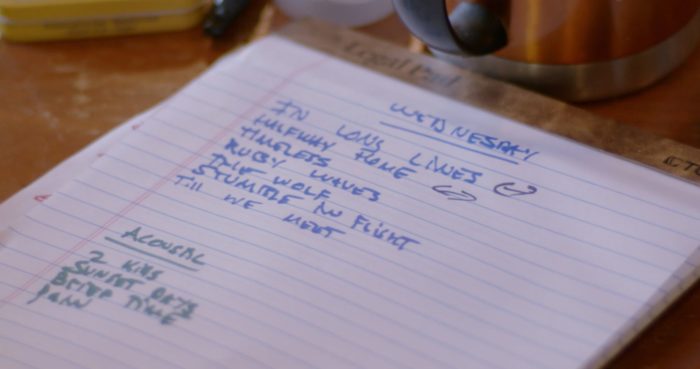

Jon Fishman: That last round of rehearsals in the dress rehearsal space, with Abbey’s production in there as well, is where we really dialed it in, two days before the first show. April 2nd was our last rehearsal in New York. And that was basically the day the order of the songs and everything came together. The first time we played the show that everyone saw on April 4th was on April 2nd. It all kind of came together right up at the finish line. It was a comfortable process.

***

The live show took a little over a year to develop. In typically backwards Phish-world fashion, the proper studio recording released midway through the tour turned out to only be an intermediate phase. In some ways, despite polish and overdubs and additional vocalists and arrangements, it was no more finished than Abbey Holmes’s sketches for the show itself.

The only element of the setlist to change throughout the run, was the solo piano pieces played each night as the band took the stage, composed by Anastasio and recorded the week before the tour on a grand piano by Jeff Tanski, otherwise known as the Ghost behind the curtain. Acting as a “one-man pit orchestra” during Phish’s “Petrichor” New Year’s piece that ushered in 2017, Tanski filled out various roles in Ghosts of the Forest, adding the sounds of owls and birds and bells. During the project’s title track, Anastasio’s voice echoes itself imperfectly with Tanski adding recorded phrases to the confusion.

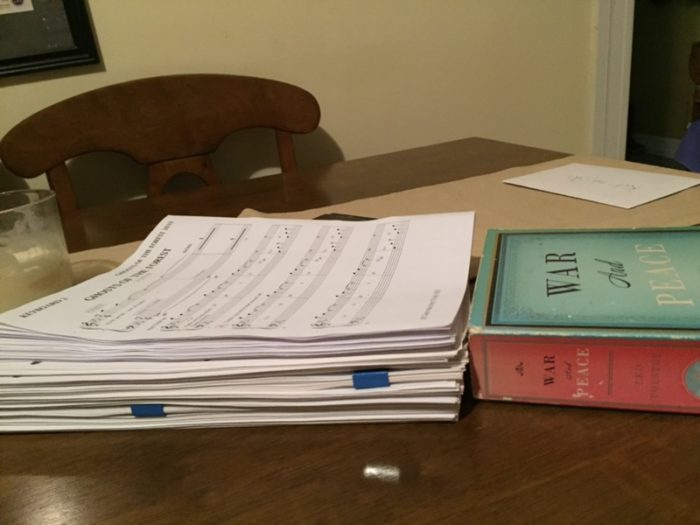

Trey Anastasio: Jeff was extremely helpful to me throughout the entire process. He was involved from the very beginning. I would make changes in the arrangements and he would make a new chart that reflected the changes. Then I would change my mind and change it again. By the time we were done, there was a stack of charts that had grown thicker than War and Peace, which Jeff and I both thought was really funny.

Abigail Holmes: During the piano pieces which started the show, the panels are very, very slowly lit, just shown as they are, and on the first note of “Ghosts of the Forest,” they shift into tints of green and leaves, as does the stage. It really changes the feel of the stage, and hopefully takes the audience on a first step into this shared place where the show will take place.

Jon Fishman: I love Chris Kuroda’s light show [for Phish], but there’s a lot of kinetic-ness to it. Whereas this was the exact opposite. It was very slow and elegant. This was more of a set piece.

Jennifer Hartswick: Part of what I loved about this whole project was having [Abbey’s] new energy in the fold. Part of the joy was seeing the visual part unfold through Abbey’s eyes. She’d done some work with Phish before, but she’s also new. It was really interesting to see her take on this kind of music. I thought it was so beautifully done, and so elegantly. It was rock and roll when it needed to be rock and roll, but it was testosterone-driven lights flashing in your face. It was a more beautiful take. She brought this breath of fresh air into it.

Jon Fishman: I liked the trajectory of the whole thing, and I like the wholeness of it. I like that there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. And I felt like I could really get behind everything that was being said. It related to my own life.

Hearing Trey sing those words every night in [in “Brief Time”] about how “we’re here for such a brief time,” I think maybe there’s an appreciation for knowing you still have enough of your youth to really put out some good some stuff, and your body still feels good.

Fifteen years from now, I’m going to be 70, and basically that goes by in a flash. I had 15 years go by on me twice already, really fucking fast. So there’s an urgency — with Kasvot Växt, or this tour. Maybe there’s a certain urgency to make hay while he can. I’m practicing now and enjoying practicing more now than I ever have. Look, I’m a lifer. I knew I was a lifer ever since I was 10 years old. But now that life’s limitations are starting to show, that’s when the lifer in you really comes out. I’ve always known I’m a lifer, but now I can see the sand running out of the hourglass.

Ray Packowski: I don’t think I thought about [my being sick] that much. I was just happy to be there, and that everything had worked out for me, that everything was good. But every time we would play that song “Friend,” I was crying at the end. It was just such a powerful song. It always just moved me, the lyrics and the music.

Trey Anastasio: “A Life Beyond The Dream” is the stone killer emotionally for me. The floodgates opened, and as was with the case with About to Run, I was writing about other people and feelings and memories from my life, beyond Chris specifically.

Fish really liked it when he heard it, and said that it conjured up thoughts that “this is the dream”, what we view as reality might be the dream.

My interpretation in writing it was far more personal, but singing it for him and hearing his interpretation gave me the confidence to allow myself to go there and be honest. I was comforted knowing that a song can conjure up different personal interpretations. I don’t want the songs to be glued to my own personal experience.

Abigail Holmes: The first night was an amazing experience. There was a room full of people who had not heard any of the music before. It was really interesting, you could feel people listening in a different way, not expecting the next sounds, but taking them in as they happened. Of course, people were listening to the streams afterwards, so no other night was quite like that.

Jon Fishman: I don’t think Phish has ever played the same show twice in a row. Maybe, if we did, we did it as a gag or something. So I didn’t really think about the experience of playing the same show every night. There’ve been a lot of times in Phish where we’ve made comments like, “Boy, it’d be really hard to go out and play the same show every night. Can you imagine how bored you’d get?”

But I really found that I loved playing the same show every night. It was a short tour, so you really felt like you wanted to improve night to night. Trey would always try to come with notes, and he would dial certain things in at rehearsals and soundcheck. And I think each time it did get better. I think every individual had certain things they wanted to do better every night. Even though it’s the same songs in the same order, it really didn’t feel the same. And I think the recordings show that, too. Different nights, different songs would stretch out or sort of find their personality.

The process was a real joy because my warm-ups were totally different. I focused on my hands and feet and just the looseness. I didn’t have to review material, like before Phish. And there something creatively freeing about not having to review as much material and being able to focus on other developmental drum things that I’ve been working on, and then trying to work that into the material.

All ‘round, I think it just makes me a better musician. I definitely had to learn a bunch of drum stuff that I can now bring to the context of Phish — just coordination stuff, certain grooves, ways of going from an upbeat to a downbeat. I can play a quarter-note triplet on my hi-hat over a seven feel now. My vocabulary increased.

Jennifer Hartswick: Playing the same set every night, I loved. Part of what Trey’s obviously known for is never playing the same set twice. But to say “this is what it is, and that’s okay,” was an eye-opening thing for him, that people would want to come see the set again. Working with him there’s always this, “oh shit!” moment, when he calls some song you haven’t played in six months or a year-and-a-half. There’s an element of stress that comes with it. And that part was completely annihilated because we knew exactly what the setlist would be. We got to dig in and be a little more comfortable. When you play the same thing every night, it starts to sink in to your DNA, and there’s a sense of ownership and comfort with the parts, and maybe a little more spontaneous enjoyment, where maybe Celisse and I will make something up in the middle of a song. I think that happened by the fourth or fifth show of the tour.

Ray Paczkowski: It always made me think of that Robert Frost quote that he said once, supposedly. At the time, he was writing in a formal way, but free verse was getting big in the ‘50s and ‘60s, where they threw all the rules out. He said “free verse is like playing tennis without a net, what’s the point?” His meaning was that where there are rules and structure, inspiration can come. I felt that way with Ghosts of the Forest. You could use your brain in a different way, and concentrate less on “How does this song go?” and more on what you can actually do in the song.

Abigail Holmes: I operated the lighting and video for all of the performances. I definitely continued to tweak and rework the both the lighting and the video, changing the lighting looks, and remaking and adding to the video pieces, especially the jam sections. Some portions of the show were fairly consistent, but the instrumental and jam sections were all executed from a manual, improvisational playback set-up for lighting and especially for video. Those portions of the show were improvised in the moment, and were different from night to night.

Ray Paczkowski: “Wider” has a fertile feel to it. It can really go anywhere. Fishman does all these different time signatures within the 4/4 and we would just kind of link up and stretch out. At the end of whatever the cycle was I would look up at Fish, who always has his head turned to the left, and I can never tell who he’s looking at. But we would always look at each other there. It was a joyful thing.

Trey Anastasio: Everything was a new song at some point, but the first night it was like 20 new songs, which is pretty bizarre. They got so much better. Some of them probably went too far and then we had to reel it back in. But you’d find places to improvise in places where you weren’t improvising before, like “Drift While You’re Sleeping,” that wasn’t happening early on. I just started to discover that “Ghosts of the Forest” could’ve been stretching out. If we’d had one more show, it was about to. More importantly, we would make tiny changes every night. Every morning, I would come in with notes or somebody else would say something, or we would adjust where the vocals go. It got so tight.

It made me sort of sad about how many songs Phish have. If you have 8,000 songs, you play ‘em once a year. It made me miss the times that we used to “You Enjoy Myself” every night. “Foam” was so tight. “Bouncing Around the Room” is probably a better example. If you listen to the Somerville Theatre [from 1991], I think that might be as good as that song ever got. We got so good at it. It was weird. And that’s such a simple song. That’s why that’s almost a better example than the complex ones.

I think that’s what I was experiencing with this — how it’s so good to be able to focus on these tunes every night and be like, ‘OK, this is the section that always throws me, I’m gonna make this much better tomorrow night.”

Jon Fishman: I was really proud of Trey in a way that I don’t know that I’ve been before. And on another level I was really grateful and proud to be part of it, and glad he asked me to be part of it. It was one of my favorite musical projects I’ve ever been involved in, in my whole life.

What I liked about it was that I was with one of my bandmates I’ve been playing with for 35 years and, on a certain level, what we did [with Ghosts of the Forest] was so totally different than what Phish does — yet, a lot of it we can bring to Phish. I hope some of these songs we play with Phish. But you’re playing with this person for a whole 35 years. And then you turn around and are able to do something that’s so totally different in a lot of ways from what you normally do together.

Celisse Henderson: Trey works differently than any artist I’ve worked with. He somehow has the ability to be so open and available to wherever something wants to go. If there’s an idea in the room he’s willing to try it. But, in the same breath, he also has a really clear cut vision for things. For how in the moment everything is, it takes so much work to actually get to a place where you can let go. That’s what I enjoyed about this style of music, changing your perspective on what your goal is onstage. The ideal thing isn’t that everything is executed in one way. It’s about the prep, and the belief that if you do all the work, it’s really about the six of us connecting and going wherever that moment goes. It really affected me a lot. There’s an aspect that’s a life lesson: You do the very best you can and you do all the work you can, but the most important thing is what’s happening right now, the thing happening in this moment. And the most exciting thing is the next moment. It was pretty revolutionary to me, it’s not the way most people work, and I think it gave me a key to a new freedom.

Tony Markellis: Trey has never been one to sit still — he’s constantly studying, learning, and absorbing new information. He forgets nothing. Every project he’s been involved in along the way combines with every past project to shape and inform the next. Ghosts of the Forest is no exception — elements from Phish, Trey Anastasio Band, Hands on a Hardbody, orchestral works, and everything else he’s ever played or heard got folded into the mix. There are Afro grooves, jams, R&B rave-ups, deep, soulful, bluesy ballads — it’s all there. Unlike most album projects, this wasn’t just a collection of songs, but rather a cathartic emotional story with an actual arc to it. I was impressed, but not surprised, that Trey managed to paint from as much of the musical palette as he did in order to tell the story.

Ghosts of the Forest was a new kind of ghost story, with such vast sadness and vast happiness that it became alive again. It grew to a full-spectrum performance, stretched between the celestial shimmer of “Beneath a Sea of Stars” and the soaring chorus of “In Long Lines,” from the existential yawp of “About to Run” to the strange and stretching groove of “Wider,” all in Anastasio’s distinct compositional voice, leaving room for through-written turns and open doors that beckon.

“Listen to that sustain,” was a common refrain of Cottrell and Anastasio’s musical friendship, particularly when listening to Jimi Hendrix. “Not just sustain of one note,” Anastasio wrote in a Facebook post after Cottrell died, “but the way Jimi always kept the energy flowing like a torrent… like whitewater rafting, how he would sustain a roaring rapid of sustain.”

If the energy flow of Ghosts of the Forest wasn’t a whitewater torrent, the sustain was just as real. This sustain was its own kind of line, the exact thread from memory to music and back, connecting the past and future by way of the nearest local now, whenever the recordings are heard, the videos are watched, and the ghosts are observed and acknowledged.

Listen to Ghosts of the Forest: Beneath a Sea of Stars. Recorded live on the final night of the tour at the Greek Theatre in Berkley, CA.